Have you reached your tipping point?

The other day, I visited my neighborhood restaurant, placed my order at the counter, tapped my card, and was prompted to tip: 18%, 20%, 25%, or a custom amount. I always help myself to drinks, seat myself, and clear my table afterward, as is common practice. Am I really tipping the same person who took my order and brought my food just ten feet to my table?

The tipping dilemma is on everyone’s mind these days. Do I tip when I drive through a Starbucks? Do I tip when I pick up a pizza I ordered over the phone? So, when did we become so tip crazy in America? Have we reached our tipping point?

Tipping started eons ago in medieval Europe. Later, when wealthy Americans traveled to Europe, they brought the practice back with them. It became widespread in the United States after the Civil War. Tipping was used to avoid paying fair wages to formerly enslaved people.

In 1991, it became federal policy to allow employers to pay servers, bartenders, and others in the industry a lower tipped minimum wage ($2.13/hour), making tipping a necessity for workers to earn a living wage rather than just a reward for good service. This hourly wage of $2.13 is still the standard today, and it must be supplemented by tips to bring total earnings up to the federal minimum wage; if not, the employer must make up the difference. And, the federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour.

Keep in mind that the minimum wage can vary by state. For example, in Colorado, the minimum wage as of January 1, 2026, is $15.16 an hour, and in Denver, it is $19.29 per hour. Some of the lowest minimum wages in the country are in the Southern states, where the minimum wage is $5.15 per hour.

In many European countries, tipping isn’t customary; a small service charge is included, and rounding up the bill is encouraged. Service workers are paid a living wage, making tipping unnecessary and sometimes even offensive, which I’ve experienced when traveling abroad.

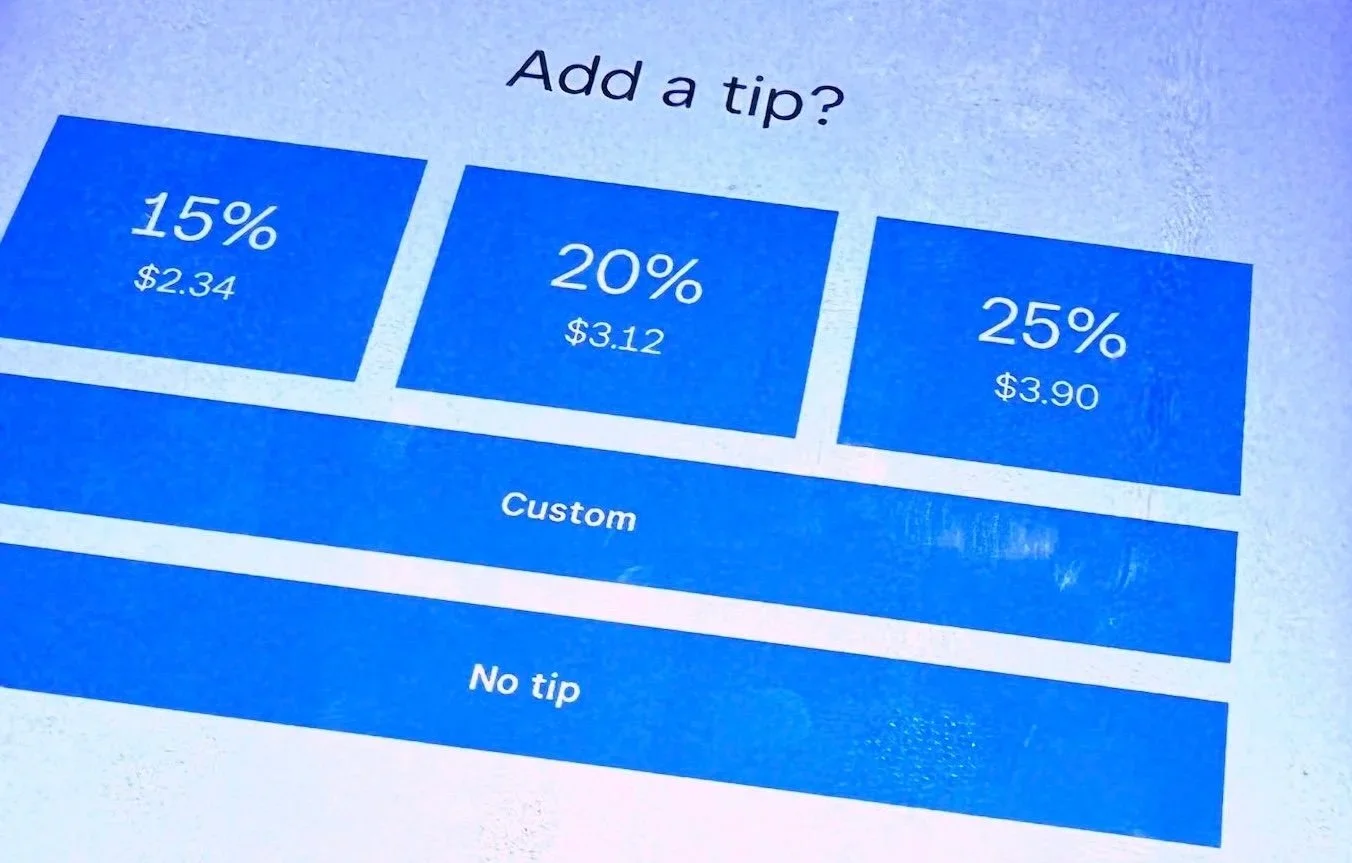

One explanation for the tipping dilemma is technology. So many establishments use iPhones, iPads, and other devices for customers to pay their bill, and they are set to prompt us to tip. Stores and restaurants lost customers during the pandemic, and began asking for higher tips to make up for lost income, and the practice continued. The trend of “tipflation” is everywhere, with digital payment screens making tipping an expected social norm, rather than an option based strictly on good service.

Call me old school, but I remember when a tip reflected the quality of service: excellent service deserved a generous tip, while poor service warranted a smaller tip. The usual range was 15% to 20%, and of course, if the service excelled, you could tip even more.

I have never understood the practice of adding an 18%-20% tip on parties of six or more. If everyone is paying separately, there may be more work involved with separate checks, but with Venmo and shared pay on Zelle, this tipping practice should go away.

A few years ago, for my birthday, we took the family out to dinner. The service charge was 22%, and the table card said tips are appreciated but not expected. I should say not. They have already added 22% to my bill. Is there any incentive to do a good job? I think not. And, as it turned out, they did not.

The last straw for me was at my local jewelry repair. I dropped off the item, paid to park, picked it up two days later, paid to park, and when it came time to pay, I was surprised to see three boxes for tipping. Are you kidding?

How do you tip? Is it based on good service, a sense of guilt, or obligation? This question lies at the heart of the current tipping dilemma—are we clear as to why we tip, or are we just following a vague social expectation?

Bit by bit, that’s all she wrote…